I recently watched Things to Come, a movie from 1936 based on the work of HG Wells. It’s not a great film, but the subtext feels prophetic. The world of the 1930s devolves into a decades-long war that destroys civilization. Warlords take over. Scientific progress is lost. When a movement rises to bring a troubled hellscape back to modernity, those in power resist change. The good guys — in this case, an army of scientists — win. They improve on what came before the apocalypse and build a utopia. However, a hundred years later, angry mobs rise up to bring scientific progress to a halt.

At every tick of history’s clock, some people will try to hold back the hands of time. No matter how good the future might be, they want to return to a time when they thought things were better, perhaps simpler. The worst part is they want to choose for you, not just themselves. I’d prefer to order off the menu myself, thanks. Leave me and that bright, hopeful future alone.

HG Wells never watched a political debate on TikTok at 3 a.m., but he saw the anti-intellectualism coming. That’s been going on for a long time, of course, but the US election year will ramp up the nonsense, and plenty. We have a rough road ahead in 2024. I won’t list all the frets, but you’ve seen the news. You know what piles on the stress. We call it doomscrolling now, but we used to call it “watching the news,” or “being aware of current events.” You’re going to hear a lot more arguing. Don’t expect well-mannered debates on the road to truth, just stubborn parroting of propaganda impenetrable to facts. Motivated reasoning is not reasonable.

You’ll also get exposed to some happy, slappy messages about how everything’s fine or will be. When crises go on too long, misery becomes normalized. The worst is when you point out an injustice and some clod mutters, “That’s nothing new.” Yeah, ya lazy dick! We should have fixed it by now, huh? But we haven’t. I fear we won’t fix much of anything.

Whatever your cause, there’s a good chance some experts are working on it. Just as surely, a bunch of idiots are maintaining the status quo or wrecking the DeLorean’s transmission by throwing Time into reverse.

So, what to do? You’re going to go to bed each night, heave a heavy sigh, and say in a thick Southern accent, “Mama’s had a day.” I say that to my wife each night because we’re going to have to hold on to our sense of humor through it all. I don’t have a solution to the climate crisis, threats of war, or a (legal) way to convince flat earthers they’re wrong. Maybe afflict the comfortable and write letters to whoever’s in charge of the circus? In your off-time, rest and recover.

Here’s my rest and recovery protocol:

- Guard your peace from those who would rob you of it.

- The usual: Sleep, eat well, and exercise.

- Put your phone down more often.

- Avoid trying to reason with unreasonable folks. Helping anyone out of ignorance is noble, but fuckwits will just waste your precious time, and time is life.

- Watch Stanley Tucci in Searching for Italy. This will reinforce your belief in the hope of a common humanity that is kind, curious, and appreciative.

- Binge-watching Modern Family will ease your mind and bring you comfort.

- If childhood was a better time for you, revel in nostalgia. I watched an episode of Barney Miller last night.

- Read fiction. It will pull you out of the forest fire that is your existence, at least for a while.

- Gather with the like-minded and enter the bar back to back, heads on a swivel.

- Laugh at determined fools. When reason fails, laughter is often the more effective weapon.

Finally, and most importantly:

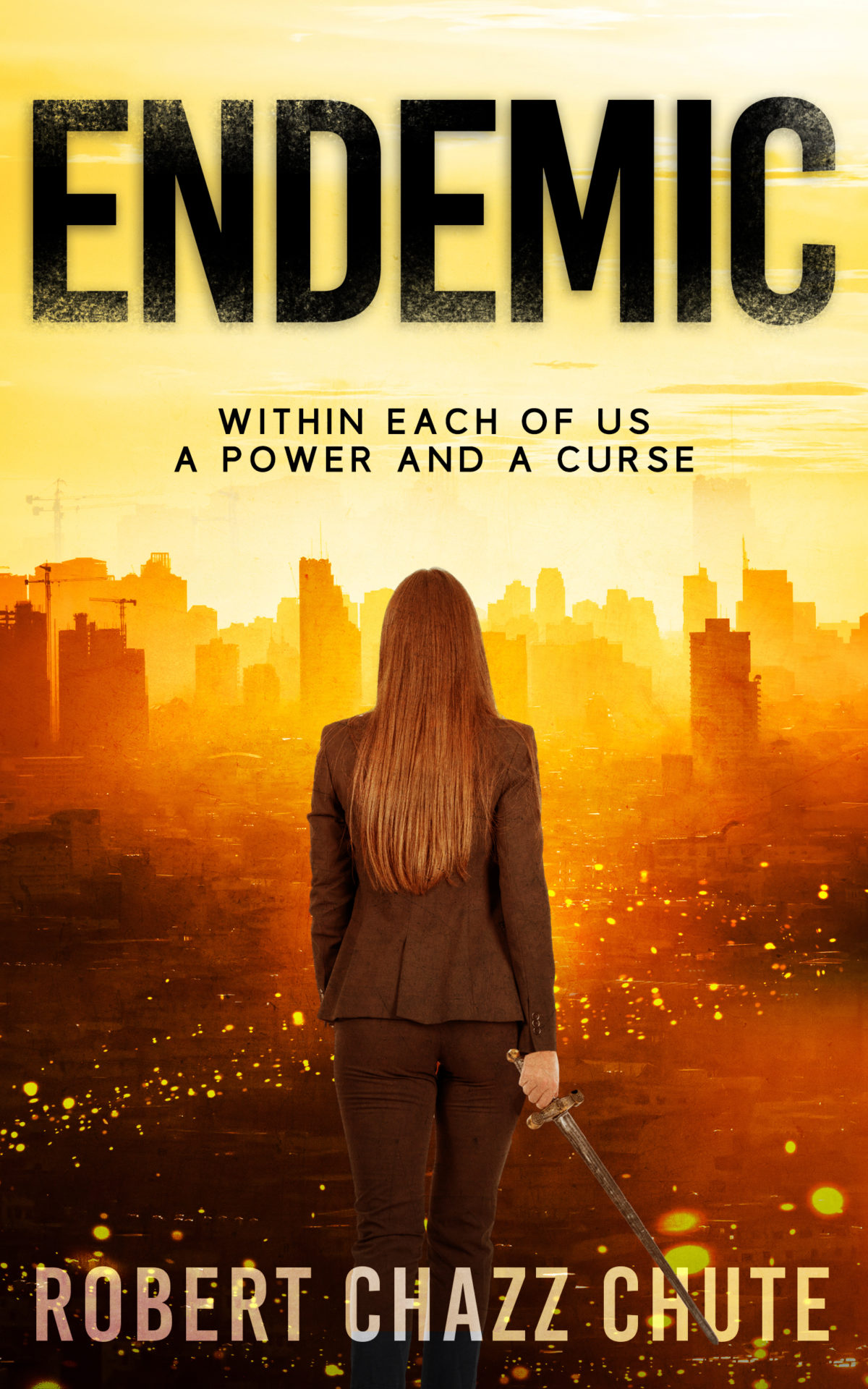

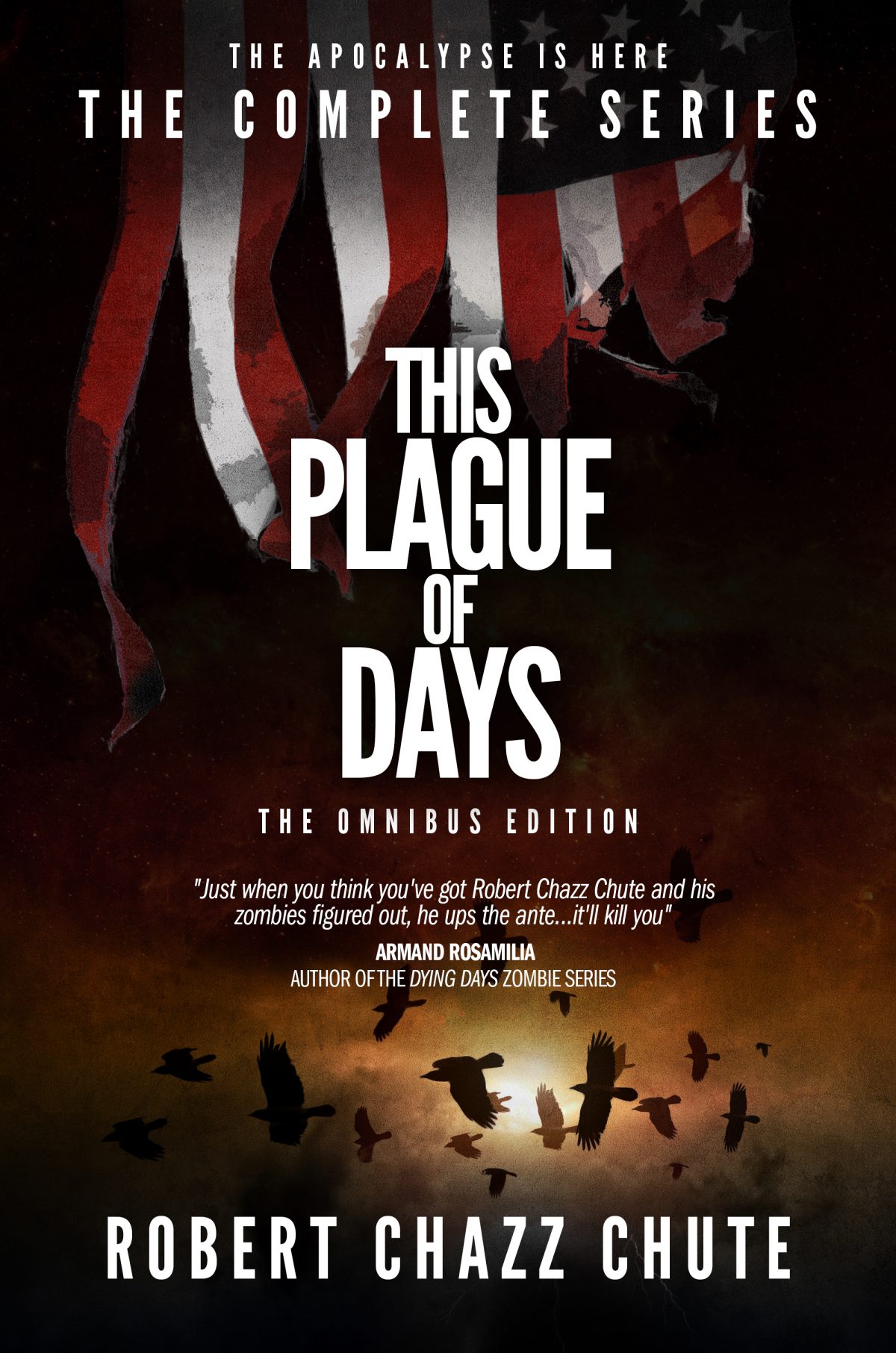

Read my fiction. Mama’s had a day, and I need money.